Retinitis Pigmentosa: When Eyesight Fades

How the Center for Ophthalmology in Tübingen, Germany, is dealing with inherited retinal degeneration.

Gene therapy has shown promise in alleviating a specific form of inherited retinal disease that leads to gradual blindness. Although this therapy enhances quality of life, it is not yet a cure.

In retinitis pigmentosa, photoreceptor cells in the retina deteriorate, causing significant vision loss by the age of 30. "There is no cure for this disease," says Prof. Dr. Katarina Stingl, who leads the consultation for hereditary retinal degenerations at the University Eye Clinic in Tübingen. However, a gene therapy (Luxturna) for a particular form of retinitis pigmentosa has been available since 2018, and it is administered at only three centers in Germany, one of which is Tübingen.

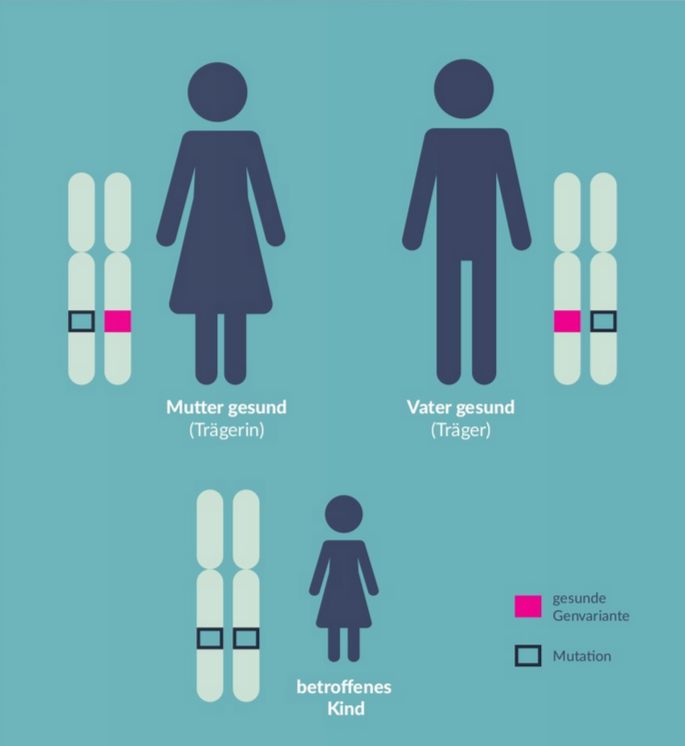

"This hereditary disease is caused by a specific genetic defect," explains Stingl. Photoreceptors, primarily the rods responsible for night vision, degrade in the retina. For photoreceptor cells to function properly, the visual pigment rhodopsin must be continuously renewed. This process requires an enzyme encoded by the RPE65 gene. In a specific form of inherited retinal degeneration, this gene is defective. If both parents carry this genetic defect, they are healthy carriers, but if the mutation is inherited from both, the child will have both gene copies defective, disrupting the visual cycle, causing the rods to fail in converting light impulses, leading to irreversible degeneration (s. the diagramm). The search for these specific gene mutations is conducted at the Institute for Ophthalmic Research in the Molecular Genetics Laboratory under the supervision of Prof. Wissinger and Dr. Kohl. "Affected individuals struggle to see in low light, have difficulty perceiving contrasts, and experience restricted fields of vision," says Stingl.

"Even with gene therapy, a cure is not possible; it can only halt the disease's progression and improve night vision. Dead photoreceptor cells are not regenerated; only the remaining ones can be reactivated," says Stingl. Therefore, early treatment, preferably in childhood, is crucial. This gene therapy, called Luxturna, delivers a functioning version of the RPE65 gene to the photoreceptor cells using a weakened virus as a vector. The therapy restores the rhodopsin cycle and reactivates the remaining photoreceptor cells. The procedure is complex, requiring an injection directly under the retina, involving the removal of the vitreous body and lifting the retina. In young patients treated in Tübingen, the operation has been successful, significantly improving night vision.

Many Genes Can Be Defective

Luxturna gene therapy is effective only for mutations in the RPE65 gene; other hereditary retinal degenerations involve different defective genes—up to 100 different genes can cause these disorders. In Tübingen, about two patients undergo this operation each year. Although most patients experience improvement, especially in their quality of life, the treatment is not permanently effective for everyone, and there are no long-term studies yet, says Stingl.

Senior physician Katarina Stingl is aware of the therapy's side effects, which other eye specialists have also reported. The main issue is cell atrophy, not at the injection site but near the blood vessels supplying the retina. "The exact cause of these atrophic lesions and their accelerated growth after gene therapy is unclear," says Stingl. It is believed that the therapy's strong impact might be the cause: "If degenerated tissue suddenly returns to normal and operates at high intensity, some areas may not cope and degenerate," explains Stingl. Tübingen is the only center worldwide attempting to counteract this atrophy with electro-stimulation. "Electro-stimulation can stimulate the release of growth factors, improve blood circulation in the retina, and curb excessive metabolic responses in peripheral areas," Stingl explains.

A study at the eye clinic aims to determine whether this treatment can yield positive results.

Excerpt and translation from an interview with Prof. Dr. K. Stingl by Paula Wagner

Here ist the link to the original Interview in German https://www.flipsnack.com/uniklinikumtuebingen/ukt-puls-02-2023/full-view.html

Fotos: Beate Armbruster

Infografik: Pietro Conte